Jamie Fiore Higgins thinks back to when her bosses at one of the world’s most powerful investment banks told her to take down her family photos from her desk.

“They didn’t want a class mom,” she says. “They wanted a commercial killer.”

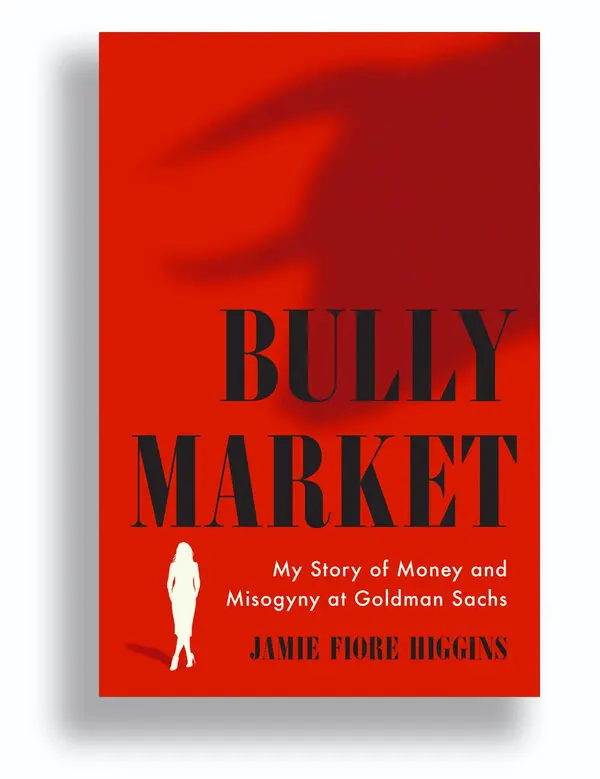

This was just one of many instances of misogyny, harassment and abuse Fiore Higgins suffered in a nearly 20-year career at Goldman Sachs. She’s authored a bestselling book about her experiences: Bully Market: My Story of Money and Misogyny at Goldman Sachs. On the eve of International Women’s Day, she sat down with Peppercomm Executive Vice President Ann Barlow for the latest in the series of Peppercomm Fireside Chats with business changemakers and thought leaders.

Fiore Higgins, who was recently named to the Financial Times’ list of the Most Influential Women of 2022, originally wanted a career as a social worker. But her parents insisted she pursue a money-making career. After immigrating to the U.S. and working day and night to cover Fiore Higgins’ medical bills and their children’s college education, they wanted a return on their investments. She applied for and was offered a job at Goldman Sachs after 40 interviews. From the beginning, she knew she was an outsider. “I showed up to orientation in a suit from TJ Maxx and shoes from Payless,” she recalls.

From her very first experiences with male colleagues at the firm, she realized the culture was problematic. Goldman Sachs had created a booklet with photos of the new hires. (She called it the firm’s version of “Facebook.”) The men in her office used it to rate the women on their sexual attractiveness. Fiore Higgins was taken aback. “They called me Sister Jamie because I wasn’t used to this,” she says.

Over the course of her career, she suffered verbal and even physical abuse. At one point, a so-called colleague pushed her up against the wall and grabbed her under the jaw.

Still, she persevered. She rose to the coveted managing director level and become the highest-ranking woman in her department. However, the burning question on everyone’s mind during the Peppercomm Fireside Chat was: “If things were so bad, why did she stay?”

Fiore Higgins clearly has thought long and hard about this. Over and above the need to support her family financially, she points out that Goldman Sachs’ culture of psychological manipulation made it very difficult to walk away. “We were taught, ‘You are nothing without Goldman Sachs money and prestige. You will never have this opportunity again.’

“Then I had a woman come up to me after one of my book talks. She said to me, ‘I know why you stayed: You were in an abusive relationship,’” she says. “Goldman Sachs puts the cult in culture. They gave us a scarcity mindset — that this was the only place to make money. They did make me feel special. I was addicted to working there, to making my family proud.”

Fiore Higgins admits now she wishes she had done more to support other women at the firm and try to change the toxic environment. However, on occasions when she did speak up, she was threatened. At one point, she witnessed a colleague use a racial epithet in a restaurant. For the first time, now in a senior role, she reported the incident to human resources after being solemnly assured her involvement would remain confidential. The next day, her manager called her in and berated her for “betraying the family.” Because the firm’s structure empowered divisions to operate somewhat autonomously, Fiore Higgins’ department was ruled like a sexist fiefdom, she explains.

Lessons for organizations today

Fiore Higgins left Goldman Sachs and now works as a trained coach, helping to guide everyone from teens to high-ranking professionals in leadership and career choices. Looking back on her experiences, she offers several tips for preventing the growth of an abusive culture in almost any organization.

Break down DEI silos: She is pleased even firms like Goldman Sachs now have DEI programs but warns that the C-suite is apt to “set it and forget it” when it comes to making true progress. DEI priorities get lost in translation when they come from the top down — and people in management roles aren’t engaged. “The partner in my group [at Goldman Sachs] set the tone,” she remembers. “This silo created by him allowed this environment to grow. [The company] took his view that everything was fine, and our business was exceptionally profitable. No one bothered to ask the questions.”

Be a humble and curious leader: For a culture to be truly inclusive, the work must flow from the top down and from the bottom up. It’s leadership’s responsibility to engage with staff to learn from them what they need, what’s working and what isn’t. She reminds leaders to be humble and admit they’re not perfect, while at the same time constantly asking questions across the organization to take the true pulse of the culture. “When you are humble and open to mistakes, you will be curious about the mistakes,” she says.

Engage and empower your people: Related to this, be intentional when you engage with your staff. Take note of whether or not they are bringing their true selves to work. Do they display family photos? Who speaks up in meetings and who stays quiet? Empower your people with the resources that a typical 25-year-old would need to build their career in your organization while feeling supported in pointing out toxic behavior and having it stopped.

Give HR a seat at the table and the power to act: Executive leaders must sanction HR to become involved in the day-to-day operations of the business to learn and study how the company’s culture comes to life. “We had compliance officers looking over our shoulders making sure the SEC wasn’t going to break down our door,” she says. “Why don’t we have culture officers? HR should be walking the floor. Welcome them to the business lines, where they can observe and be present.”

In the end, every leader has a duty to drive conversation and address this problem because it impacts everyone.

“Workplace toxicity affects all of us,” Fiore Higgins says. “But there’s still a reluctance to get our hands dirty with this topic. If we can’t find space to talk about it, how are we going to change it?”

Photo by Daniel Lloyd Blunk-Fernández on Unsplash